Difference between revisions of "Building brewing water with dissolved chalk"

(→Why dissolve chalk) |

(→References) |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | In order to build brewing water with temporary hardness (alkalinity and calcium hardness), chalk (CaCO<sub>3</sub>) is needed. Chalk, however, is not very soluble in water and most of what is added remains suspended or settles to the bottom. This article describes how chalk can be dissolved if so desired. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | In order | + | |

= About chalk and the carbonate system = | = About chalk and the carbonate system = | ||

| − | If you do not want to be bothered with the chemistry behind dissolving chalk you can safely skip ahead. | + | |- |

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''If you do not want to be bothered with the chemistry behind dissolving chalk you can safely skip ahead.'' | ||

| − | Chalk CaCO<sub>3</sub> is | + | Chalk, also known as calcium carbonate (CaCO<sub>3</sub>), is a salt of carbonic acid. It's ions are calcium (Ca<sup>2+</sup>) and carbonate (CO<sub>3</sub><sup>2-</sup>). If we know one thing about chalk in brewing it is that it doesn't dissolve very well in water. This is because the solubility product between calcium and carbonate is a very small number. Chemists write it like this: |

:[Ca<sup>2+</sup>]*[CO<sub>3</sub><sup>2-</sup>] ≤ K<sub>sp</sub> = 3.36×10<sup>-9</sup> | :[Ca<sup>2+</sup>]*[CO<sub>3</sub><sup>2-</sup>] ≤ K<sub>sp</sub> = 3.36×10<sup>-9</sup> | ||

| − | The names in brackets ([]) stand for the concentration of the particular | + | The names in brackets ([]) stand for the concentration of the particular ions. What that formula means is that water can only hold calcium and carbonate in solution as long as the product of their concentrations is less or equal to 3.36×10<sup>-9</sup> (0.00000000336). If the product is greater that that calcium carbonate will precipitate until enough calcium and carbonate have been removed from the water to satisfy the equation. |

| − | But how can we get calcium carbonate | + | But how can we get calcium carbonate dissolved in water? We do this by removing the carbonate that chalk adds when it dissolves. To understand this we have to take a look at carbonic acid and the carbonate system. Carbonic acid is formed when carbon dioxide is dissolved in water. Not all the dissolved carbon dioxide (CO<sub>2</sub>) will form carbonic acid but some does according to this chemical equation: |

:CO<sub>2</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O ↔ H<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3</sub> | :CO<sub>2</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O ↔ H<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3</sub> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 23: | ||

[[Image:Carbonic_acid_to_carbonate.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 1''' - The transformation of carbonic acid to carbonate over bicarbonate and back to carbonic acid]] | [[Image:Carbonic_acid_to_carbonate.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 1''' - The transformation of carbonic acid to carbonate over bicarbonate and back to carbonic acid]] | ||

| − | The "↔" means that there is a constant back and forth between both sides. I.e. carbonic acid is formed and falls apart into CO<sub>2</sub> and water constantly. But on average there is always a portion of CO<sub>2</sub> bound as carbonic acid. The interesting thing about carbonic acid is that it is a weak acid that can loose up to two protons (H<sup>+</sup>). We | + | The "↔" means that there is a constant back and forth between both sides. I.e. carbonic acid is formed and falls apart into CO<sub>2</sub> and water constantly. But on average there is always a specific portion of CO<sub>2</sub> bound as carbonic acid. The interesting thing about carbonic acid is that it is a weak acid that can loose up to two protons (H<sup>+</sup>). We looked at weak acids in [[An_Overview_of_pH#Weak_acids_and_bases|Weak Acids and Bases]] where we saw that the loss or acceptance of protons depends on the pH of the environment. When a carbonic acid molecule looses one proton it becomes a bicarbonate ion: |

:H<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3</sub> ↔ HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> + H<sup>+</sup> | :H<sub>2</sub>CO<sub>3</sub> ↔ HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> + H<sup>+</sup> | ||

| − | + | This process is reversible. I.e. if a bicarbonate ion picks up a proton it becomes carbonic acid. | |

| + | |||

| + | When a bicarbonate ion looses a proton it becomes carbonate: | ||

:HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> ↔ CO<sub>3</sub><sup>2-</sup> + H<sup>+</sup> | :HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> ↔ CO<sub>3</sub><sup>2-</sup> + H<sup>+</sup> | ||

| − | That process is illustrated in Figure 1. As mentioned earlier, the relative concentration of these 3 carbonate species, as they are called, [deLange] depends on | + | That process is illustrated in Figure 1. As mentioned earlier, the relative concentration of these 3 carbonate species, as they are called, [deLange] depends on pH since it is pH which determines how much H<sup>+</sup> is available. The more there is the more carbonic acid will exist and the less there is the more carbonate will be present. Figure 2 plots these relative concentration as % of the total carbonic acid + bicarbonate + carbonate amount over a pH range of 0 to 14. |

| − | [[Image:Carbonic_acid_dissociation.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 2''' - The relative concentration of carbonic acid, bicarbonate and carbonate based on the pH of the solution]] | + | [[Image:Carbonic_acid_dissociation.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 2''' - The relative concentration of carbonic acid, bicarbonate and carbonate based on the pH of the solution. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) recommends drinking water to have a pH between 6.5 and 8.5 [EPA]]] |

| − | But how does this tie into dissolving chalk? Well, earlier we saw that we need to | + | But how does this tie into dissolving chalk? Well, earlier we saw that we need to remove the carbonate that dissolving chalk contributes to the water in order to allow the chalk to dissolve. This is done by converting the carbonate into bicarbonate. This process consumes protons. It is these protons that we have to supply to dissolve more chalk than the water can hold without any help. |

| − | To get these protons we need to add acid. After all that's what an acid does, it adds protons and | + | To get these protons we need to add an acid. After all that's what an acid does, it adds protons and as a result lowers the pH of a solution. For acids we have basically two choices carbonic acid or other acids. Let's have a look at what happens when we add an acid other than carbonic acid. Hydrochloric acid for example which, in water, falls apart into a proton (H<sup>+</sup>) and a chloride ion (Cl<sup>-</sup>): |

:2H<sup>+</sup> + 2Cl<sup>-</sup> + CaCO<sub>3</sub> → H<sub>2</sub>O + CO<sub>2</sub> + 2Cl<sup>-</sup> + Ca<sup>2+</sup> | :2H<sup>+</sup> + 2Cl<sup>-</sup> + CaCO<sub>3</sub> → H<sub>2</sub>O + CO<sub>2</sub> + 2Cl<sup>-</sup> + Ca<sup>2+</sup> | ||

| − | + | The result of the reaction between hydrochloric acid and the chalk is water, CO<sub>2</sub> (which escapes), chloride (Cl<sup>-</sup>) and calcium (Ca<sup>2+</sup>). Looking at these results, we could have done this water modification much simpler by just adding calcium chloride as a salt. One of the reasons why we want to dissolve chalk in water is increasing its alkalinity which is caused by bicarbonate and carbonate ions. If the bicarbonate or carbonate content of the water doesn't change its alkalinity won't change either. | |

Acids other than carbonic acid don't work. So what about carbonic acid. When carbonic acids becomes bicarbonate it looses a proton which can convert the carbonate ions added by the chalk to bicarbonate. Here is what this looks like: | Acids other than carbonic acid don't work. So what about carbonic acid. When carbonic acids becomes bicarbonate it looses a proton which can convert the carbonate ions added by the chalk to bicarbonate. Here is what this looks like: | ||

| Line 47: | Line 50: | ||

:HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> + H<sup>+</sup> + CaCO<sub>3</sub> → Ca<sup>2+</sup> + 2HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> | :HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> + H<sup>+</sup> + CaCO<sub>3</sub> → Ca<sup>2+</sup> + 2HCO<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> | ||

| − | The chalk molecule fell apart into a calcium ion and | + | The chalk molecule fell apart into a calcium ion and a bicarbonate ion. The other bicarbonate ion comes from the carbonic acids which lost a proton. Because this proton was lost to dissolving chalk we can say that the one molecule of chalk was also responsible for the creation of that bicarbonate ion. In the end one molecule of chalk, when dissolved with carbonic acid, creates one calcium ion and two bicarbonate ions. |

| − | [[Image:CaCO3_solubility.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 3''' - The CO2 pressure needed to dissolve a certain concentration of chalk in water. Note that both the x and the y axis are labeled with a logarithmic scale]] | + | [[Image:CaCO3_solubility.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 3''' - The CO2 pressure needed to dissolve a certain concentration of chalk in water. Note that both the x and the y axis are labeled with a logarithmic scale (data source [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calcium_carbonate#Solubility Wikipedia - Calcium Carbonate Solubility]]] |

| − | Getting | + | Getting carbonic acid into water is as easy as adding CO<sub>2</sub> to it. We saw earlier how some of the CO<sub>2</sub> dissolved in water forms carbonic acid. To dissolve a substantial amount of chalk, however, much more CO<sub>2</sub> than the atmosphere is providing is needed. From carbonating beer we know that the CO<sub>2</sub> content of beer depends on its temperature and head space CO<sub>2</sub> pressure. The same is true for water: the higher the CO<sub>2</sub> pressure the higher the amount of dissolved CO<sub>2</sub>. Using a number of chemical equilibrium equations the relation between the CO<sub>2</sub> pressure over water can be correlated with the amount of chalk that can be dissolved in that water [deLange]. Figure 3 shows how the CO<sub>2</sub> pressure correlates with the amount of chalk water can hold. Note that both the x and the y axis are logarithmic and that the seemingly linear relationship is actually close to a cubic function. In practical terms that means that dissolving more than ~800 ppm CaCO<sub>3</sub> in water is unpractical since it requires a substantial amount of CO2 pressure which we don't generally have access to. This needs to be kept in mind for the proposed procedure of dissolving chalk which initially dissolves all the chalk in a volume smaller than the actual brewing water volume. |

| + | |||

| + | | valign="top" | [[Image:Icon_science.gif|link=|alt={Geeky Stuff}]] [[Image:Icon_inner_workings.gif|link=|alt={How Things Work}]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="clear:both;"></div> | ||

=Why dissolve chalk= | =Why dissolve chalk= | ||

| − | [[Image:Chart_pH_over_chalk_concentration.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 4''' - ]] | + | [[Image:Chart_pH_over_chalk_concentration.gif|frame|right|'''Figure 4''' - The mash pH for mashes made with distilled water and various levels of chalk addition. One set of experiments dissolved the chalk with CO2 while the other set left the chalk undissolved]] |

| − | Now that we know how to dissolve chalk in water we need to ask us why | + | Now that we know how to dissolve chalk in water we need to ask us why put forth this effort? Especially since the mash will provide an acid environment that should dissolve any chalk that wasn't dissolved in the water. At mash pH (~5.5) less than 0.00005 % of the carbo species are carbonate. |

| − | For some reason, however, [http://braukaiser.com/documents/effect_of_water_and_grist_on_mash_pH.pdf mash pH experiments] conducted with suspended and dissolved chalk showed that suspended, i.e. undissolved chalk, is limited in its ability to raise the mash pH. This is shown in Figure 4. | + | For some reason, however, [http://braukaiser.com/documents/effect_of_water_and_grist_on_mash_pH.pdf mash pH experiments] conducted with suspended and dissolved chalk showed that suspended, i.e. undissolved chalk, is limited in its ability to raise the mash pH. This is shown in Figure 4. Undissolved chalk was unable to raise the mash pH by more than 0.2 units. This was the case for both Pilsner and Munich malt mashes and does not seem to depend on the acidity of the malt. Dissolved chalk, on the other hand, showed a nice fairly linear relationship between chalk concentration and pH. |

| − | I tested this in side-by-side where I brewed a [http://braukaiser.com/lifetype2/index.php?op=ViewArticle&articleId=132&blogId=1 Schwarzbier] with water that had suspended chalk and water that had dissolved chalk. Based on the mash pH research I knew that, when dissolving it, I could use only half the chalk and would still get the same mash pH. That was validated in the experiment. | + | I tested this in a side-by-side experiment where I brewed a [http://braukaiser.com/lifetype2/index.php?op=ViewArticle&articleId=132&blogId=1 Schwarzbier] with water that had suspended chalk and water that had dissolved chalk. Based on the mash pH research I knew that, when dissolving it, I could use only half the chalk and would still get the same mash pH. That was validated in the experiment. |

| − | + | If you want to brew according to the German ''Reinheitsgebot'' you will have to dissolve the chalk, since the addition of salts in the mash or the use of water that doesn't meet drinking water standards is not allowed. | |

| − | All this being said, dissolving chalk to build brewing water should be considered a technique for the advanced brewer. I have brewed many excellent beers by adding chalk directly to the mash or by not dissolving it in brewing water and just recently started to dissolve the chalk for my brewing water. | + | All this being said, dissolving chalk to build brewing water should be considered a technique for the advanced brewer. I have brewed many excellent beers by adding chalk directly to the mash or by not dissolving it in brewing water and only just recently started to dissolve the chalk for my brewing water. As with many other techniques, a brewer will have to see for him or herself if it is worth the additional effort. |

=How to dissolve chalk using carbonated water= | =How to dissolve chalk using carbonated water= | ||

| − | To brew an upcoming batch of [[Kaiser Alt]] I want to mimic the water profile of the city of Düsseldorf where most of the Alts are brewed in Germany. One of the most well known Alt breweries | + | To brew an upcoming batch of [[Kaiser Alt]] I want to mimic the water profile of the city of Düsseldorf where most of the Alts are brewed in Germany. One of the most well known Alt breweries, ''Zum Uereige'', however, does not use city water. According to this [http://www.dooyoo.de/bier/uerige-alt/296389/ on-line statement] the brewing water for that brewery comes from their own deep well. The Düsseldorf public water, on the other hand, is essentially cleaned and treated water from the river ''Rhein''. |

The current water report for Düsseldorf is available on-line: [http://www.swd-ag.de/privatkunden/wasser/trinkwasseranalyse.php Water report Düsseldorf] and upon calculating the residual alkalinity for that water one finds 108 ppm as CaCO<sub>3</sub> or 6.1 dH (dH is German Hardness). Such a residual alkalinity is well suited for brewing a dark amber beer like an Alt and I assume that most Alt breweries use city water without any water treatment. | The current water report for Düsseldorf is available on-line: [http://www.swd-ag.de/privatkunden/wasser/trinkwasseranalyse.php Water report Düsseldorf] and upon calculating the residual alkalinity for that water one finds 108 ppm as CaCO<sub>3</sub> or 6.1 dH (dH is German Hardness). Such a residual alkalinity is well suited for brewing a dark amber beer like an Alt and I assume that most Alt breweries use city water without any water treatment. | ||

| Line 76: | Line 85: | ||

| | | | ||

| − | = | + | = The process step by step = |

| − | In order to calculate the addition of dissolved chalk | + | == Calculating the salt additions== |

| + | |||

| + | In order to calculate the addition of dissolved chalk correctly you need a brewing water spreadsheet that supports dissolved chalk. Most of the available spreadsheets don't since they assume that each chalk molecule contributes only one bicarbonate ion. You can test this by adding 1 g of chalk to 1 l (3.78g to 1 gal) of water. If the resulting alkalinity (not residual alkalinity) is 490-500 ppm as CaCO3 only half the chalk's alkalinity potential is considered and the chalk is not supposed to be dissolved in the water. My water spread sheet, [http://braukaiser.com/documents/Kaiser_water_calculator.xls Kaiser_water_calculator.xls], supports both dissolved and undissolved chalk in brewing water. In general, when dissolving chalk only half the amount of chalk is needed to build a water with the same residual alkalinity as a water build with undissolved chalk. | ||

| valign="top" | [[Image:Icon_brewing_advice.gif|link=|alt={Practical Brewing Advice}]] | | valign="top" | [[Image:Icon_brewing_advice.gif|link=|alt={Practical Brewing Advice}]] | ||

| Line 84: | Line 95: | ||

| | | | ||

| − | ==Step 1== | + | ===Step 1=== |

| − | On the "advanced" work sheet enter the starting water profile. I use reverse osmosis water which is very soft | + | On the "advanced" work sheet enter the starting water profile. I use reverse osmosis water which is very soft and for which I have a water analysis. If you are using reverse osmosis water and don't have an analysis simply leave the fields for the starting water profile 0. Due to the low ion concentration compared to the final ion concentration of the brewing water the error will be minimal and too small to matter. |

[[Image:Dissolving_chalk_base_water.gif|center]] | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_base_water.gif|center]] | ||

| − | ==Step 2== | + | ===Step 2=== |

| − | With an eye on the resulting water profile (section below or right most column) enter concentrations of brewing salts. Rather then entering the final amounts of salts needed and considering the volume of water that will be treated salts are entered as ppm (equivalent to mg/l). This makes the "water recipe" independent of the volume of water that needs to be treated. Once the water volume is known the spreadsheet calculates the required amounts of salts and displays them in a later section. | + | With an eye on the resulting water profile (section below or right most column) enter concentrations of brewing salts. Rather then entering the final amounts of salts needed and considering the volume of water that will be treated, salts are entered as ppm (equivalent to mg/l). This makes the "water recipe" independent of the volume of water that needs to be treated. Once the water volume is known the spreadsheet calculates the required amounts of salts and displays them in a later section. |

[[Image:Dissolving_chalk_salts.gif|center]] | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_salts.gif|center]] | ||

| − | ==Step 3== | + | ===Step 3=== |

| − | Check the resulting water profile. If you compare this profile to the Düsseldorf water report | + | Check the resulting water profile. If you compare this profile to the Düsseldorf water report which was referenced earlier you'll find it to be a very close match. This is not always possible since we brewers don't have all combinations of cations (positive ions) and anions (negative ions), i.e. salts, available to us. In those cases focus on matching the residual alkalinity, calcium, sulfate and chloride content of the water. |

[[Image:Dissolving_chalk_resulting_water.gif|center]] | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_resulting_water.gif|center]] | ||

| − | ==Step 4== | + | ===Step 4=== |

| − | Now it is time to enter the total water volume and | + | Now it is time to enter the total water volume and strike water volume. The spreadsheet will calculate the sparge water volume from these numbers. You should also enter the grist weight which will allow for the the calculation of mash thickness. Mash thickness is important for making a mash pH estimation from beer color and residual alkalinity since mash thickness determines the pH shift that a given residual alkalinity causes. |

| − | Once you enter the beer color in SRM and how much of the specialty malts are roasted malts an estimate of the mash pH can be made. In this case it is 5.5 and well within the acceptable range of 5.2 - 5.7. The lower right hand corner of the mash pH section also shows estimates for the residual | + | Once you enter the beer color in SRM and how much of the specialty malts are roasted malts an estimate of the mash pH can be made. In this case it is 5.5 and well within the acceptable range of 5.2 - 5.7. The lower right hand corner of the mash pH section also shows estimates for the residual alkalinity that would be necessary to reach a mash pH of 5.2, 5.4 and 5.6 respectively. The large range from ~-100 to ~200 ppm as CaCO<sub>3</sub> shows how wide of a range of brewing waters could be used to brew a 20 SRM beer with a mash thickness of 4 l/kg (~2 qt/lb) |

[[Image:Dissolving_chalk_pH_estimate.gif|center]] | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_pH_estimate.gif|center]] | ||

| − | ==Step 5== | + | ===Step 5=== |

| − | Using the water volumes specified earlier, the amounts of salts needed | + | Using the water volumes specified earlier, the amounts of salts needed are calculated. Because I don't have the ability to treat all the water at once I have to treat mash and sparge water separately. But for those able to treat all the needed water at once the amounts needed for the total volume are also given. |

| − | Of interest for dissolving chalk is the "dissolving chalk" section. Here you enter the volume of water that the chalk | + | Of interest for dissolving chalk is the "dissolving chalk" section. Here you enter the volume of water that the chalk will be dissolved in and the spreadsheet estimates the minimal CO<sub>2</sub> pressure needed to dissolve the chalk. You'll quickly find that the relation between chalk concentration and pressure is not linear and that the pressure quickly shoots up once you exceed about 750-800 ppm. As a result this concentration of chalk is generally the practical limit and to dissolve more chalk you need to dissolve it in a larger mount of water. |

| − | If possible I like to dissolve my chalk additions in 2 l soda bottles and in this case it will be possible. Using 1.9 l to dissolve the mash water addition and 1.6 l to dissolve the sparge water addition I need only 1.55 bar and 1.38 bar respectively. Those pressure numbers are absolute which means that they include atmospheric pressure and that I have to use >0.55 bar and >0.38 bar as the setting on the regulator. A CO<sub>2</sub> pressure regulator measures | + | If possible I like to dissolve my chalk additions in 2 l soda bottles and in this case it will be possible. Using 1.9 l to dissolve the mash water addition and 1.6 l to dissolve the sparge water addition I need only 1.55 bar (23 psi) and 1.38 bar (20 psi)respectively. Those pressure numbers are absolute which means that they include atmospheric pressure and that I have to use >0.55 bar (> 8 psi) and >0.38 bar (> 6 psi) as the setting on the regulator. A CO<sub>2</sub> pressure regulator measures pressure in excess of the atmospheric pressure. |

[[Image:Dissolving_chalk_salt_amounts.gif|center]] | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_salt_amounts.gif|center]] | ||

| − | + | ==Building the brewing water== | |

| − | + | ||

| − | =Building the brewing water= | + | |

{| style="width:800px" | {| style="width:800px" | ||

| − | | colspan="2" align="center" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_needed_items.jpg|frame|'''Figure | + | | colspan="2" align="center" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_needed_items.jpg|frame|'''Figure 5''' - These are the needed items: 2 liter soda bottles, carbonator cap, funnel, weighed salts and water. I mark the bottles with batch number and if the "brine" is for mash or sparge water treatment]] |

| − | | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_add_salts.jpg|frame|'''Figure | + | | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_add_salts.jpg|frame|'''Figure 6''' - Set the funnel into the bottle and dump the salts into the funnel]] |

|} | |} | ||

{| style="width:800px" | {| style="width:800px" | ||

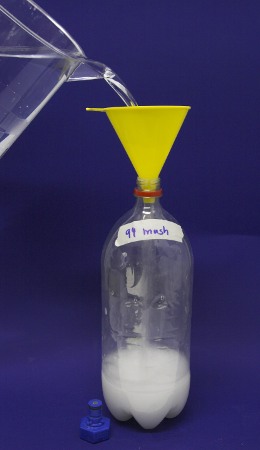

| − | | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_add_water.jpg|frame|'''Figure | + | | valign="top" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_add_water.jpg|frame|'''Figure 7''' - Add water. The water will wash any salts, that got stuck in the funnel, into the bottle. Even if close to 2 l water are needed, don't fill the bottle all the way yet. Leaving a headspace makes carbonating the water easier]] |

| − | | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_remove_air.jpg|frame|'''Figure | + | | valign="top" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_remove_air.jpg|frame|'''Figure 8''' - Add the carbonator cap, press it open and squeeze out all the air. Removing all the air and replacing it with CO<sub>2</sub> will make carbonation much more effective since the headspace will be completely filled with CO<sub>2</sub>]] |

| − | | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_hook_up_CO2.jpg|frame|'''Figure | + | | valign="top" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_hook_up_CO2.jpg|frame|'''Figure 9''' - Hook up the CO<sub>2</sub> bottle via a regulator and shake the bottle to carbonate the water. Keep shaking until no more CO<sub>2</sub> is flowing into the bottle. Once carbonated top off with more water, if necessary, and carbonate again. Repeat the process for the other bottle(s)]] |

|} | |} | ||

{| style="width:800px" | {| style="width:800px" | ||

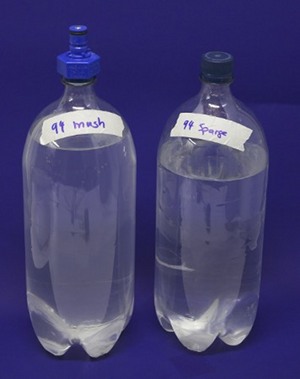

| − | | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_clear_water.jpg|frame|'''Figure | + | | valign="top" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_clear_water.jpg|frame|'''Figure 10''' - After standing for a while the water should clear. A slight haze may remain but there should not be a large amount of chalk sediment that turns the water cloudy once shaken up. If the water doesn't clear divide the contents evenly between two bottles, add water and carbonate again. Maybe the chalk concentration was too high to be dissolved by the available CO<sub>2</sub> pressure]] |

| + | | valign="top" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_strike_water.jpg|frame|'''Figure 11''' - The day before or on brewday I add the salt brine to the rest of the reverse osmosis water to get the desired volume of strike water and later the same for the sparge water. While CO<sub>2</sub> is now able to escape from the water the chalk will not come out of solution very quickly. It has been diluted so much, that it will take a long time for enough CO<sub>2</sub> to escape in order for chalk to precipitate again. You'll see more CO<sub>2</sub> escape while heating the water but since it is not boiled, enough CO<sub>2</sub> remains in solution to keep the chalk dissolved]] | ||

| + | | valign="top" | [[Image:Dissolving_chalk_pH.jpg|frame|'''Figure 12''' - If you test the pH of the water you will find that it is lower than what you expect from fairly alkaline water. This low pH is the result of an excess of carbonic acid but the pH does not affect the alkalinity of the water. When I tested the hardness and alkalinity with a [[At_home_water_testing|GH&KH test kit]] I found a hardness of 15 dH (270 ppm as CaCO<sub>3</sub>) and an alkalinity of 10 dH (180 ppm as CaCO<sub>3</sub>). Which matched the expectations close enough.]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | An alternative vessel for dissolving chalk are corny kegs. Their advantage is being able to hold larger volumes of water and as a result the chalk concentration can be much lower. With that the needed CO<sub>2</sub> pressure is substantially lower. The main disadvantage is the difficulty of visual inspection since it requires drawing a sample. But due the lower CO<sub>2</sub> pressure that is needed it is much more likely that all chalk gets dissolved in the larger water volume in a corny keg compared to the 2 liter limit in a soda bottle. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =References= | ||

| + | |||

| + | :[deLange] A. J. deLange, [http://ajdel.wetnewf.org:81/Brewing_articles/Cerevesia/Final_galley Alkalinity, Hardness, Residual Alkalinity and Malt Phosphate: Factors in the Establishment of Mash pH], 2004 | ||

| + | :[EPA] epa.gov, [http://www.epa.gov/ogwdw000/consumer/2ndstandards.html Secondary Drinking Water Regulations] | ||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:00, 2 March 2010

|

In order to build brewing water with temporary hardness (alkalinity and calcium hardness), chalk (CaCO3) is needed. Chalk, however, is not very soluble in water and most of what is added remains suspended or settles to the bottom. This article describes how chalk can be dissolved if so desired. ContentsAbout chalk and the carbonate system | |||||||||

|

If you do not want to be bothered with the chemistry behind dissolving chalk you can safely skip ahead. Chalk, also known as calcium carbonate (CaCO3), is a salt of carbonic acid. It's ions are calcium (Ca2+) and carbonate (CO32-). If we know one thing about chalk in brewing it is that it doesn't dissolve very well in water. This is because the solubility product between calcium and carbonate is a very small number. Chemists write it like this:

The names in brackets ([]) stand for the concentration of the particular ions. What that formula means is that water can only hold calcium and carbonate in solution as long as the product of their concentrations is less or equal to 3.36×10-9 (0.00000000336). If the product is greater that that calcium carbonate will precipitate until enough calcium and carbonate have been removed from the water to satisfy the equation. But how can we get calcium carbonate dissolved in water? We do this by removing the carbonate that chalk adds when it dissolves. To understand this we have to take a look at carbonic acid and the carbonate system. Carbonic acid is formed when carbon dioxide is dissolved in water. Not all the dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2) will form carbonic acid but some does according to this chemical equation:

The "↔" means that there is a constant back and forth between both sides. I.e. carbonic acid is formed and falls apart into CO2 and water constantly. But on average there is always a specific portion of CO2 bound as carbonic acid. The interesting thing about carbonic acid is that it is a weak acid that can loose up to two protons (H+). We looked at weak acids in Weak Acids and Bases where we saw that the loss or acceptance of protons depends on the pH of the environment. When a carbonic acid molecule looses one proton it becomes a bicarbonate ion:

This process is reversible. I.e. if a bicarbonate ion picks up a proton it becomes carbonic acid. When a bicarbonate ion looses a proton it becomes carbonate:

That process is illustrated in Figure 1. As mentioned earlier, the relative concentration of these 3 carbonate species, as they are called, [deLange] depends on pH since it is pH which determines how much H+ is available. The more there is the more carbonic acid will exist and the less there is the more carbonate will be present. Figure 2 plots these relative concentration as % of the total carbonic acid + bicarbonate + carbonate amount over a pH range of 0 to 14. But how does this tie into dissolving chalk? Well, earlier we saw that we need to remove the carbonate that dissolving chalk contributes to the water in order to allow the chalk to dissolve. This is done by converting the carbonate into bicarbonate. This process consumes protons. It is these protons that we have to supply to dissolve more chalk than the water can hold without any help. To get these protons we need to add an acid. After all that's what an acid does, it adds protons and as a result lowers the pH of a solution. For acids we have basically two choices carbonic acid or other acids. Let's have a look at what happens when we add an acid other than carbonic acid. Hydrochloric acid for example which, in water, falls apart into a proton (H+) and a chloride ion (Cl-):

The result of the reaction between hydrochloric acid and the chalk is water, CO2 (which escapes), chloride (Cl-) and calcium (Ca2+). Looking at these results, we could have done this water modification much simpler by just adding calcium chloride as a salt. One of the reasons why we want to dissolve chalk in water is increasing its alkalinity which is caused by bicarbonate and carbonate ions. If the bicarbonate or carbonate content of the water doesn't change its alkalinity won't change either. Acids other than carbonic acid don't work. So what about carbonic acid. When carbonic acids becomes bicarbonate it looses a proton which can convert the carbonate ions added by the chalk to bicarbonate. Here is what this looks like:

The chalk molecule fell apart into a calcium ion and a bicarbonate ion. The other bicarbonate ion comes from the carbonic acids which lost a proton. Because this proton was lost to dissolving chalk we can say that the one molecule of chalk was also responsible for the creation of that bicarbonate ion. In the end one molecule of chalk, when dissolved with carbonic acid, creates one calcium ion and two bicarbonate ions.  Figure 3 - The CO2 pressure needed to dissolve a certain concentration of chalk in water. Note that both the x and the y axis are labeled with a logarithmic scale (data source Wikipedia - Calcium Carbonate Solubility Getting carbonic acid into water is as easy as adding CO2 to it. We saw earlier how some of the CO2 dissolved in water forms carbonic acid. To dissolve a substantial amount of chalk, however, much more CO2 than the atmosphere is providing is needed. From carbonating beer we know that the CO2 content of beer depends on its temperature and head space CO2 pressure. The same is true for water: the higher the CO2 pressure the higher the amount of dissolved CO2. Using a number of chemical equilibrium equations the relation between the CO2 pressure over water can be correlated with the amount of chalk that can be dissolved in that water [deLange]. Figure 3 shows how the CO2 pressure correlates with the amount of chalk water can hold. Note that both the x and the y axis are logarithmic and that the seemingly linear relationship is actually close to a cubic function. In practical terms that means that dissolving more than ~800 ppm CaCO3 in water is unpractical since it requires a substantial amount of CO2 pressure which we don't generally have access to. This needs to be kept in mind for the proposed procedure of dissolving chalk which initially dissolves all the chalk in a volume smaller than the actual brewing water volume. |

| ||||||||

Why dissolve chalkNow that we know how to dissolve chalk in water we need to ask us why put forth this effort? Especially since the mash will provide an acid environment that should dissolve any chalk that wasn't dissolved in the water. At mash pH (~5.5) less than 0.00005 % of the carbo species are carbonate. For some reason, however, mash pH experiments conducted with suspended and dissolved chalk showed that suspended, i.e. undissolved chalk, is limited in its ability to raise the mash pH. This is shown in Figure 4. Undissolved chalk was unable to raise the mash pH by more than 0.2 units. This was the case for both Pilsner and Munich malt mashes and does not seem to depend on the acidity of the malt. Dissolved chalk, on the other hand, showed a nice fairly linear relationship between chalk concentration and pH. I tested this in a side-by-side experiment where I brewed a Schwarzbier with water that had suspended chalk and water that had dissolved chalk. Based on the mash pH research I knew that, when dissolving it, I could use only half the chalk and would still get the same mash pH. That was validated in the experiment. If you want to brew according to the German Reinheitsgebot you will have to dissolve the chalk, since the addition of salts in the mash or the use of water that doesn't meet drinking water standards is not allowed. All this being said, dissolving chalk to build brewing water should be considered a technique for the advanced brewer. I have brewed many excellent beers by adding chalk directly to the mash or by not dissolving it in brewing water and only just recently started to dissolve the chalk for my brewing water. As with many other techniques, a brewer will have to see for him or herself if it is worth the additional effort. How to dissolve chalk using carbonated waterTo brew an upcoming batch of Kaiser Alt I want to mimic the water profile of the city of Düsseldorf where most of the Alts are brewed in Germany. One of the most well known Alt breweries, Zum Uereige, however, does not use city water. According to this on-line statement the brewing water for that brewery comes from their own deep well. The Düsseldorf public water, on the other hand, is essentially cleaned and treated water from the river Rhein. The current water report for Düsseldorf is available on-line: Water report Düsseldorf and upon calculating the residual alkalinity for that water one finds 108 ppm as CaCO3 or 6.1 dH (dH is German Hardness). Such a residual alkalinity is well suited for brewing a dark amber beer like an Alt and I assume that most Alt breweries use city water without any water treatment. | |||||||||

The process step by stepCalculating the salt additionsIn order to calculate the addition of dissolved chalk correctly you need a brewing water spreadsheet that supports dissolved chalk. Most of the available spreadsheets don't since they assume that each chalk molecule contributes only one bicarbonate ion. You can test this by adding 1 g of chalk to 1 l (3.78g to 1 gal) of water. If the resulting alkalinity (not residual alkalinity) is 490-500 ppm as CaCO3 only half the chalk's alkalinity potential is considered and the chalk is not supposed to be dissolved in the water. My water spread sheet, Kaiser_water_calculator.xls, supports both dissolved and undissolved chalk in brewing water. In general, when dissolving chalk only half the amount of chalk is needed to build a water with the same residual alkalinity as a water build with undissolved chalk. |

| ||||||||

Step 1On the "advanced" work sheet enter the starting water profile. I use reverse osmosis water which is very soft and for which I have a water analysis. If you are using reverse osmosis water and don't have an analysis simply leave the fields for the starting water profile 0. Due to the low ion concentration compared to the final ion concentration of the brewing water the error will be minimal and too small to matter. Step 2With an eye on the resulting water profile (section below or right most column) enter concentrations of brewing salts. Rather then entering the final amounts of salts needed and considering the volume of water that will be treated, salts are entered as ppm (equivalent to mg/l). This makes the "water recipe" independent of the volume of water that needs to be treated. Once the water volume is known the spreadsheet calculates the required amounts of salts and displays them in a later section. Step 3Check the resulting water profile. If you compare this profile to the Düsseldorf water report which was referenced earlier you'll find it to be a very close match. This is not always possible since we brewers don't have all combinations of cations (positive ions) and anions (negative ions), i.e. salts, available to us. In those cases focus on matching the residual alkalinity, calcium, sulfate and chloride content of the water. Step 4Now it is time to enter the total water volume and strike water volume. The spreadsheet will calculate the sparge water volume from these numbers. You should also enter the grist weight which will allow for the the calculation of mash thickness. Mash thickness is important for making a mash pH estimation from beer color and residual alkalinity since mash thickness determines the pH shift that a given residual alkalinity causes. Once you enter the beer color in SRM and how much of the specialty malts are roasted malts an estimate of the mash pH can be made. In this case it is 5.5 and well within the acceptable range of 5.2 - 5.7. The lower right hand corner of the mash pH section also shows estimates for the residual alkalinity that would be necessary to reach a mash pH of 5.2, 5.4 and 5.6 respectively. The large range from ~-100 to ~200 ppm as CaCO3 shows how wide of a range of brewing waters could be used to brew a 20 SRM beer with a mash thickness of 4 l/kg (~2 qt/lb) Step 5Using the water volumes specified earlier, the amounts of salts needed are calculated. Because I don't have the ability to treat all the water at once I have to treat mash and sparge water separately. But for those able to treat all the needed water at once the amounts needed for the total volume are also given. Of interest for dissolving chalk is the "dissolving chalk" section. Here you enter the volume of water that the chalk will be dissolved in and the spreadsheet estimates the minimal CO2 pressure needed to dissolve the chalk. You'll quickly find that the relation between chalk concentration and pressure is not linear and that the pressure quickly shoots up once you exceed about 750-800 ppm. As a result this concentration of chalk is generally the practical limit and to dissolve more chalk you need to dissolve it in a larger mount of water. If possible I like to dissolve my chalk additions in 2 l soda bottles and in this case it will be possible. Using 1.9 l to dissolve the mash water addition and 1.6 l to dissolve the sparge water addition I need only 1.55 bar (23 psi) and 1.38 bar (20 psi)respectively. Those pressure numbers are absolute which means that they include atmospheric pressure and that I have to use >0.55 bar (> 8 psi) and >0.38 bar (> 6 psi) as the setting on the regulator. A CO2 pressure regulator measures pressure in excess of the atmospheric pressure. Building the brewing water

An alternative vessel for dissolving chalk are corny kegs. Their advantage is being able to hold larger volumes of water and as a result the chalk concentration can be much lower. With that the needed CO2 pressure is substantially lower. The main disadvantage is the difficulty of visual inspection since it requires drawing a sample. But due the lower CO2 pressure that is needed it is much more likely that all chalk gets dissolved in the larger water volume in a corny keg compared to the 2 liter limit in a soda bottle.

References

| |||||||||